Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America

Peniel E. Joseph

Henry Holt & Company

2006

399 pages

Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour is a historical survey of ‘black power’, an umbrella term applicable to social movements dedicated to empowering black communities in 20th century United States. The book charts a path from figures such as the pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey to the millenarian Nation of Islam, through to the American Civil Rights movement (and the specific organizations that constituted it) up to the Black Panthers. Author Peniel E. Joseph (a professor of history working at Tufts University in Massachusetts) is as thorough as possible with his material charting the splintered path each leader and organization takes to their conclusion. His narrative peters out as it moves into the 80s when it focused mostly on mainstream political figures such as Jesse Jackson (who was, himself, a civil rights activist as a young man), as a kind of apotheosis to the far more radical past that allowed figures such as him to move closer to the moderate centre.

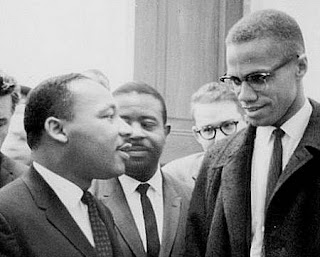

Of course, the narrative is dominated by all of the figures that would be expected: Malcom X, Martin Luther King Jr, Stokely Charmical, and finally the Black Panther leadership (Cleaver, Seale, Newton, etc). There are, of course, a large number of other important figures but these are the names that drive Joseph’s (and possibly any) narrative of American black activism. There are also a number of binaries at play in Joseph’s narrative: Marxist vs protestant influence, separatist vs integrationist, non-violent civil disobedieance vs armed resistance/violent struggle. One thing that I hadn’t quite noticed until after completing the book is that it is primarily focused on the radical edge of black social movements. Figures such as W.E.B. DuBois and organizations like his NAACP are discussed, of course, but are given far less attention than groups like the SNCC or the Black Panthers. Also, the book has a detailed bibliography subdivided into publication type and the index is structured so that subtopics of major topics are indexed.

Showing posts with label sncc. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sncc. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Saturday, July 9, 2011

john lewis, civil rights movement - book - 1998 - Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement

Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement

John Lewis with Michael D’Orso

Simon and Schuster

1998

496 pages

Walking With the Wind is a memoir, by progressive US Congressman John Lewis, of a life perpetually engaged in political struggle. D'Orso and Lewis' book was named one of the "50 Books of our Times" by Newsweek magazine in 2009, and it won the Robert F Kennedy book award in 1999. Lewis is currently the elected member of the US house of Congress for the State of Georgia’s 5th district, which covers most of the city of Atlanta. As a young man Lewis was heavily involved in the Civil Rights movement, he worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and attained the position of Chairman to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the major organizations involved in propelling that movement forward. After the movement dissipated, Lewis entered mainstream politics, first working on the Robert Kennedy campaign for the Democratic Party primaries in 1968, and in 1977 a failed bid at a congressional seat. In 1987 Lewis won the election for the congressional seat that he currently holds.

Here is an example of the contemporary John Lewis.

Lewis’ memoir recalls his impoverished youth (he was the child of sharecroppers) and his early development of a social consciousness that compelled him to eventually struggle for civil rights. The first few chapters of the memoir begin with Lewis discussing a recent visit to a southern city, and then proceeding into his memories of the movement that pertain to that locale. This structure does not hold through the entirety of the book, but it sufficiently anchors the voice of the author in the contemporary period, in case the reader forgets. Lewis is looking back on his participation in a political movement that sucessfully changed society to the extent that he, a black man, could now hold a position of political power in the American South.

Lewis’ recalls all of the major events of the Civil Rights movement; the freedom rides, the sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters, the violence, the indifference of law enforcement to the suffering of marchers at the hands of white mobs, the 1963 March on Washington DC, the tensions between black and white activists, the tensions between adherents to nonviolence and activists who advocated the use of violence and King's assassination. Lewis also recalls many of the little struggles, those that took place within the movement for individual power or for the purpose of advancing a particular shift in ideology or strategy. What makes Lewis’ book relevant to the literature on the civil rights movement is that it comes from the voice of a participant, and in particular a participant who used the momentum he gained from his participation in the movement to achieve mainstream political power in order to continue his struggle and to be a symbol of the movement’s success.

Walking with the Wind is replete with his unique thoughts on the movement events. He describes first hand the experiences of being physically attacked and then arrested by police. He discusses the speech he had prepared for that 1963 March on Washington D.C., the event at which Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” address. While Martin Luther King strongly uttering that one line has become appropriated as an iconic image of human (or perhaps merely ‘American’) potential, John Lewis delivered his own speech earlier in the day. Lewis recalls that King was among a group of men who pressured Lewis to soften his rhetoric. Such anecdotes from a high profile insider of the movement add inflection to the historical events that are commonly known as a series of images. Lewis was very critical of state power in their indifference (if not assistance) to the suffering of the American south’s black population, and furthermore he was a strict adherent to nonviolent activism (despite his frequent arrests and injuries). This strength of character pervades his memoir and colours his remembrances of interactions with individuals such as Malcolm X and his successor as SNCC chairman, Stokely Charmichael. Furthermore, Lewis’ memoir is relevant for inserting the names of forgotten activists back into the discourse of civil rights movement history.

To the extent that Lewis’ record speaks for itself, the reader of Walking With the Wind does not have to wonder whether or not the activist was, in 1998, altering his memories or his past attitudes to serve his present political career. Lewis is currently a fearless progressive politician who has fought for issues such as the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation, and a bill supporting the right for conscientious objectors to be exempt from paying taxes towards military support.

Walking with the Wind ends with a description of Lewis’ career in mainstream politics and a list of issues that continue to plague African-American communities. An interesting aspect to this final section of Lewis’ text is that he continues to use the langauge of radical politics as a United States congressman. He makes the call to ‘agitate, agitate, agitate!’ when discussing solutions to the unresolved problems of the poor communities he serves. Lewis and D'orso's book represents the life of a man who continues to fight for the same moral good he has always struggled for, and with the same force of language and character regardless of the status he holds.

John Lewis with Michael D’Orso

Simon and Schuster

1998

496 pages

Walking With the Wind is a memoir, by progressive US Congressman John Lewis, of a life perpetually engaged in political struggle. D'Orso and Lewis' book was named one of the "50 Books of our Times" by Newsweek magazine in 2009, and it won the Robert F Kennedy book award in 1999. Lewis is currently the elected member of the US house of Congress for the State of Georgia’s 5th district, which covers most of the city of Atlanta. As a young man Lewis was heavily involved in the Civil Rights movement, he worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and attained the position of Chairman to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the major organizations involved in propelling that movement forward. After the movement dissipated, Lewis entered mainstream politics, first working on the Robert Kennedy campaign for the Democratic Party primaries in 1968, and in 1977 a failed bid at a congressional seat. In 1987 Lewis won the election for the congressional seat that he currently holds.

Here is an example of the contemporary John Lewis.

Lewis’ memoir recalls his impoverished youth (he was the child of sharecroppers) and his early development of a social consciousness that compelled him to eventually struggle for civil rights. The first few chapters of the memoir begin with Lewis discussing a recent visit to a southern city, and then proceeding into his memories of the movement that pertain to that locale. This structure does not hold through the entirety of the book, but it sufficiently anchors the voice of the author in the contemporary period, in case the reader forgets. Lewis is looking back on his participation in a political movement that sucessfully changed society to the extent that he, a black man, could now hold a position of political power in the American South.

Lewis’ recalls all of the major events of the Civil Rights movement; the freedom rides, the sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters, the violence, the indifference of law enforcement to the suffering of marchers at the hands of white mobs, the 1963 March on Washington DC, the tensions between black and white activists, the tensions between adherents to nonviolence and activists who advocated the use of violence and King's assassination. Lewis also recalls many of the little struggles, those that took place within the movement for individual power or for the purpose of advancing a particular shift in ideology or strategy. What makes Lewis’ book relevant to the literature on the civil rights movement is that it comes from the voice of a participant, and in particular a participant who used the momentum he gained from his participation in the movement to achieve mainstream political power in order to continue his struggle and to be a symbol of the movement’s success.

Walking with the Wind is replete with his unique thoughts on the movement events. He describes first hand the experiences of being physically attacked and then arrested by police. He discusses the speech he had prepared for that 1963 March on Washington D.C., the event at which Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” address. While Martin Luther King strongly uttering that one line has become appropriated as an iconic image of human (or perhaps merely ‘American’) potential, John Lewis delivered his own speech earlier in the day. Lewis recalls that King was among a group of men who pressured Lewis to soften his rhetoric. Such anecdotes from a high profile insider of the movement add inflection to the historical events that are commonly known as a series of images. Lewis was very critical of state power in their indifference (if not assistance) to the suffering of the American south’s black population, and furthermore he was a strict adherent to nonviolent activism (despite his frequent arrests and injuries). This strength of character pervades his memoir and colours his remembrances of interactions with individuals such as Malcolm X and his successor as SNCC chairman, Stokely Charmichael. Furthermore, Lewis’ memoir is relevant for inserting the names of forgotten activists back into the discourse of civil rights movement history.

To the extent that Lewis’ record speaks for itself, the reader of Walking With the Wind does not have to wonder whether or not the activist was, in 1998, altering his memories or his past attitudes to serve his present political career. Lewis is currently a fearless progressive politician who has fought for issues such as the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation, and a bill supporting the right for conscientious objectors to be exempt from paying taxes towards military support.

Walking with the Wind ends with a description of Lewis’ career in mainstream politics and a list of issues that continue to plague African-American communities. An interesting aspect to this final section of Lewis’ text is that he continues to use the langauge of radical politics as a United States congressman. He makes the call to ‘agitate, agitate, agitate!’ when discussing solutions to the unresolved problems of the poor communities he serves. Lewis and D'orso's book represents the life of a man who continues to fight for the same moral good he has always struggled for, and with the same force of language and character regardless of the status he holds.

Saturday, July 2, 2011

abbie hoffman - book - 1998 - Steal This Dream: Abbie Hoffman and the Countercultural Revolution in America

Steal This Dream: Abbie Hoffman and the Countercultural Revolution in America

Larry Sloman

Doubleday

1998

437 pages

Steal This Dream: Abbie Hoffman and the Countercultural Revolution in America is an oral biography of 1960s radical leader, Abbie Hoffman. The book’s author, Larry Sloman, was an active agent of the 1960s counterculture in some capacity, and statements by himself appear in this text to reflect his own familiarity with Hoffman. Like any oral biography, Steal This Dream is composed recorded words of hundreds of Sloman’s interview subjects. This book is one of several biographies about Abbie Hoffman, including Marty Jezer’s Abbie Hoffman: American Rebel, For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman by Jonah Raskin, Run Run Run: The Lives of Abbie Hoffman by Abbie’s brother, Jack Hoffman, and finally Abbie’s autobiography, Soon to be a Major Motion Picture. All of these biographies were written by people who knew Hoffman personally, and perhaps with the exception of Abbie’s brother, all were by individuals who were directly involved in the counterculture that Abbie helped to develop. Steal This Dream’s is unique among the Hoffman literature in that it is an oral biography.

Author Larry Sloman is probably best known as a collaborator of Howard Stern, with whom Sloman authored Private Parts and Miss America. Sloman has also written a number of biographies of figures such as Bob Dylan, Anthony Keidas, and most recently, Harry Houdini. Sloman also authored a book about the social history of marijuana titled, Refer Madness: A History of Marijuana. He holds a masters degree in Deviance and Criminology, which appears to carry into his work as an author and journalist, as much of his work focuses on figures who play in the margins of culture and society. While a number of Sloman’s books play on issues of nonconformism and deviance, Steal This Dream, in its lack of criticality of its subjects, appears to be a culmination of a wave of nostalgia for the radical 1960s that carried through the late 1980s and 1990s.

Steal This Dream covers all of the important events of Hoffman’s life, as told by his friends and enemies (including some of the law enforcement personnel he had encounters with). His childhood, his unhappy first marriage, his Freedom Ride experience, his anti-war activism and related pranks, Chicago 68’ and the subsequent trial, his cocaine bust and flight underground, his resurfacing, his environmental activism, his career as a campus speaker and his death are discussed. With oral biographies there is a lack of critical distance, as the people in the subject’s life tend to rosily wax nostalgic or vent their anger, often over minor details and irrelevant anecdotes, (Abbie’s brother Jack, for example, appears fixated on the radical prankster’s sexual life). The book is most interesting when Abbie’s self-mythologizing is challenged, for example, when Bob Zellner (an SNCC activist) stated that Hoffman exaggerated his involvement in the civil rights movement. I believe that for a figure who wrote so much about himself, such commentary is fair and welcome to a researcher, but primarily much of what is critical of Hoffman is focused on minor details rather than on deconstruction of his acts or statements.

This book’s value to a researcher may be primarily in its sources and their quotations. The statements of many notable figures of the 1960s appear in this book, and while much of what they say is about Hoffman, many statements are also just ruminations on the events of the decade. Additionally, insights into rivalries between groups, such as the tension between the Diggers and the Yippies, for example, can be found in Sloman’s text, and may help give depth to some of the attitudes different radical factions held towards one another at the time.

An unfortunate dimension to the experience of reading Steal This Dream is that the connection an interview subject has to Abbie can easily be forgotten. The text has an appendix that lists all of the interviewees and their status as of the time of publication, but a similar appendix that lists their role in the 1960s or in Hoffman’s life would have been extremely helpful in making the book searchable. Interviewee names may disappear and then reappear later, and it is easy for the reader (i.e., me) to forget who they were if they are not a well known ex-radical. Sloman’s subtitle for his text suggests that this book is a history of the American counterculture, from its civil rights movement beginnings through to the 1980s environmental movement. The book would be useful as a historical text if it contained some means by which a reader may search it quickly.

Abbie Hoffman committed suicide in 1989. There’s a quote, given by New York City poetry maverick John Giorno towards the end of the book, where he quoted William Burroughs as saying, “He really let us down.” Many of the final statements of Sloman’s book were in response to Burrough’s shorthand eulogy. Mike Rossman (I’ve lost track of his connection to Hoffman) said “If anything, Burroughs’ is a reiteration of the attitude which, introjected, helped to kill Abbie. This demand that the man’s life should not be his own... it appears to me to be an inhuman demand.” It may have been an inhuman demand, but Sloman’s biography describes a man who loved life as a media figure, and entered the media in order to make similar demands of others.

Larry Sloman

Doubleday

1998

437 pages

Steal This Dream: Abbie Hoffman and the Countercultural Revolution in America is an oral biography of 1960s radical leader, Abbie Hoffman. The book’s author, Larry Sloman, was an active agent of the 1960s counterculture in some capacity, and statements by himself appear in this text to reflect his own familiarity with Hoffman. Like any oral biography, Steal This Dream is composed recorded words of hundreds of Sloman’s interview subjects. This book is one of several biographies about Abbie Hoffman, including Marty Jezer’s Abbie Hoffman: American Rebel, For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman by Jonah Raskin, Run Run Run: The Lives of Abbie Hoffman by Abbie’s brother, Jack Hoffman, and finally Abbie’s autobiography, Soon to be a Major Motion Picture. All of these biographies were written by people who knew Hoffman personally, and perhaps with the exception of Abbie’s brother, all were by individuals who were directly involved in the counterculture that Abbie helped to develop. Steal This Dream’s is unique among the Hoffman literature in that it is an oral biography.

Author Larry Sloman is probably best known as a collaborator of Howard Stern, with whom Sloman authored Private Parts and Miss America. Sloman has also written a number of biographies of figures such as Bob Dylan, Anthony Keidas, and most recently, Harry Houdini. Sloman also authored a book about the social history of marijuana titled, Refer Madness: A History of Marijuana. He holds a masters degree in Deviance and Criminology, which appears to carry into his work as an author and journalist, as much of his work focuses on figures who play in the margins of culture and society. While a number of Sloman’s books play on issues of nonconformism and deviance, Steal This Dream, in its lack of criticality of its subjects, appears to be a culmination of a wave of nostalgia for the radical 1960s that carried through the late 1980s and 1990s.

Sloman is frequently the invisible hand whose name appears smaller than the celebrity he collaborates with even though it is often his labour that makes it appear as though a rock star has actually sat down and written a book. Steal This Dream is unique among his own ouevre, and among the Abbie Hoffman books, as it is an oral biography, meaning that Sloman interviewed scores of people who knew the man, and structured their resultant statements into an account of his life from this myriad of perspectives. The printed statements, often many appear to a single page, may be supplemented by statements made by Hoffman himself from interviews he gave during the 1960s and by images of him or events related to the events being discussed. This is the basic structure of the book, and the structure of almost any oral biography.

The text of this book exists in two time periods. The statements of people, speaking from the 1990s but looking back on the event that was Abbie Hoffman, and excerpted statements given by Hoffman from various points in his life. This approach highlights an issue with the oral biography regarding the aspect of distance. Hoffman (deceased since 1989) can only speak through his media appearances from the times being discussed by all of the other textual sources. As is noted by many of his friends in Steal This Dream, Hoffman was a master media figure, and was always attempting to present an image of himself that balanced an appearance of mischievous playfulness as well as radical seriousness. This representation is manifest in the quotations by Hoffman selected by Sloman, and such quotes were primarily used to fill out the details of a particular event under discussion. Abbie's included statements are already conditioned by his approach to media appearance. Meanwhile everyone else is looking back on events that occured 20 to 40 years ago from a situation where The Sixties have been apotheosized as a new golden age for radical political activity and alternative living (the age which inspired Theodore Roszak to coin the term ‘counterculture’). Sloman’s subjects are speaking from a sense of their own historical relevance - and are discussing Abbie Hoffman in a nostalgic manner - often to demonstrate their own appearance and importance in that history. Additionally they are looking back upon a completed life. We now know that Hoffman suffered from bipolar disorder and the people who knew him may now give enlightened comments on that component of his personality. Steal This Dream is not a source for finding how his friends and associates understood his bipolar-related behavior at the time.

Steal This Dream covers all of the important events of Hoffman’s life, as told by his friends and enemies (including some of the law enforcement personnel he had encounters with). His childhood, his unhappy first marriage, his Freedom Ride experience, his anti-war activism and related pranks, Chicago 68’ and the subsequent trial, his cocaine bust and flight underground, his resurfacing, his environmental activism, his career as a campus speaker and his death are discussed. With oral biographies there is a lack of critical distance, as the people in the subject’s life tend to rosily wax nostalgic or vent their anger, often over minor details and irrelevant anecdotes, (Abbie’s brother Jack, for example, appears fixated on the radical prankster’s sexual life). The book is most interesting when Abbie’s self-mythologizing is challenged, for example, when Bob Zellner (an SNCC activist) stated that Hoffman exaggerated his involvement in the civil rights movement. I believe that for a figure who wrote so much about himself, such commentary is fair and welcome to a researcher, but primarily much of what is critical of Hoffman is focused on minor details rather than on deconstruction of his acts or statements.

This book’s value to a researcher may be primarily in its sources and their quotations. The statements of many notable figures of the 1960s appear in this book, and while much of what they say is about Hoffman, many statements are also just ruminations on the events of the decade. Additionally, insights into rivalries between groups, such as the tension between the Diggers and the Yippies, for example, can be found in Sloman’s text, and may help give depth to some of the attitudes different radical factions held towards one another at the time.

An unfortunate dimension to the experience of reading Steal This Dream is that the connection an interview subject has to Abbie can easily be forgotten. The text has an appendix that lists all of the interviewees and their status as of the time of publication, but a similar appendix that lists their role in the 1960s or in Hoffman’s life would have been extremely helpful in making the book searchable. Interviewee names may disappear and then reappear later, and it is easy for the reader (i.e., me) to forget who they were if they are not a well known ex-radical. Sloman’s subtitle for his text suggests that this book is a history of the American counterculture, from its civil rights movement beginnings through to the 1980s environmental movement. The book would be useful as a historical text if it contained some means by which a reader may search it quickly.

Abbie Hoffman committed suicide in 1989. There’s a quote, given by New York City poetry maverick John Giorno towards the end of the book, where he quoted William Burroughs as saying, “He really let us down.” Many of the final statements of Sloman’s book were in response to Burrough’s shorthand eulogy. Mike Rossman (I’ve lost track of his connection to Hoffman) said “If anything, Burroughs’ is a reiteration of the attitude which, introjected, helped to kill Abbie. This demand that the man’s life should not be his own... it appears to me to be an inhuman demand.” It may have been an inhuman demand, but Sloman’s biography describes a man who loved life as a media figure, and entered the media in order to make similar demands of others.

Labels:

1960s,

abbie hoffman,

chicago 68,

chicago 8 trial,

civil rights movement,

emmet grogan,

environmental movement,

jerry rubin,

oral biography,

psychedelia,

sncc,

timothy leary,

united states,

yippies

Thursday, June 16, 2011

martin luther king jr, civil rights movement - book - 2008 - King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop

King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop

Harvard Sitkoff

Hill and Wang

2008

288 Pages

Greetings, I borrowed King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop from the Robarts Library at the University of Toronto.

Harvard Sitkoff is an American Historian who taught at the University of New Hampshire where he is currently serving as professor emeritus. Sitkoff is a scholar of the American Civil Rights movement and he has written a number of books on that subject. King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop is his most recent book, and his only biography of a movement figure.

King is a short biography of the celebrated Civil Rights leader. Many scholars have devoted an enormous amount of energy describing King’s life, and if a researcher does not require a highly detailed account of a segment of King’s life then Sitkoff’s concise biography is probably sufficient. This volume devotes the last seven pages of its text to the Sanitation Worker's strike in Memphis, for example, which was the issue King was dealing with at the time of his assassination. Meanwhile the book Going Down Jericho Road by Michael K. Honey, a text that deals solely with the events pertaining to the Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike, is over 400 pages in length. While Sitkoff’s text is quite strong, my only grievance with the book is that he presents the bibliography as a ‘bibliographic essay’, where the references are strung together in paragraphs rather than listed as individual entries. I find this form of referencing to be irritating to search through as the biblographic essay is much more dense, textually, than the traditional form of listed bibliographic references.

King: Pilgrimage to the Mounaintop depicts King as a man who realized his talent for speaking, and was thrust by his parishioners into the spotlight. Sitkoff creates the sense that King was one of those men who was created by history, he had the talents to deal with the issues of his time, but it was his time that formed him into the leader he was. One of the primary value of the book is that it depicts King as a man whose life was fraught with failures. King was motivated to try, the success of his endeavours was never assured, and it was often blocked by circumstance. Despite his Nobel laureate status and his ascension to the position of an unofficial founding father for the current age, King’s life was not a string of relentless success. Sitkoff instead presents King as a man who did not falter in his path, despite occasional failure, towards an egalitarian vision of social harmony.

King adopted Gandhi’s principles of non-violent resistance and applied them to the struggle to attain equal rights for poor blacks in the United States. King worked directly with many impoverished black communities, with varying degrees of achievment, although it was his early work in Selma and Montgomery Alabama that brought him the most success and attention. The civil rights leader’s later successes came from not wavering from his dedication to non-violence. Sitkoff presents King’s voice as diminishing towards the end of the 1960s, as the rise of a black power radicalism emerged with the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, and other radical factions. Converse to King and many of the early civil rights groups, the radical organizations and leaders held much more liberal attitudes towards violence, often preaching it as an unwelcome but necessary part of the racial struggle in America. King developed rhetoric to demonstrate a sympathetic understanding of a black will to violence, but he never condoned such action. According to Sitkoff, however, King was constantly criticized for his proximity to the pro-violent groups, King was still the major figure of the movement even though his adherence to peaceful resistance was losing ground within the overall movement. Shortly before his death, King was held responsible for a march turned riot in Memphis that resulted in the death of a teenager. King was accused by a white media establishment of failing to keep the peace, but King simply could not contain the anger of the poor communities he was trying to organize.

Sitkoff portrays King as an individual who was constantly feeling the tension between the constraining power of the establishment, the detractions of other civil rights factions, the white opposition, and the needs of the poor. Furthermore, Sitkoff presents King as a man who was given to vice as a coping mechanism for dealing with the stresses of his position. The leader’s life was fraught with fear, as King frequently received death threats, and Sitkoff tries to represent the inner battle King must have fought to overcome these terrors. In so doing, Sitkoff creates a glimmer of the sense of what the experience of being a leader of history, may actually feel like.

In current popular culture, King's life has primarily been reduced to the speech he delivered in Washington DC in 1963. Perhaps his image has been flattened further, to merely the line "I have a dream!" When isolated, that line is merely a statement of desire for a boundless future, and can be inserted into a history of such expressions. The line is depoliticized when its isolated from the rest of the speech, and decontextualized when, for example, no one has to remember that, several days after that speech was delivered, a bomb exploded in a predominantly African-American church in Burmingham Alabama, killing four little girls. Now, in popular culture, the moment that line was delivered is almost cast as the moment racial tension broke and race was transcended in America. Media apparitions such as the far-right mouthpiece, Glenn Beck freely appropriate King’s image for their own purposes. Sitkoff’s brief biography is unlikely to successfully compete for dominance with any pop-culture constructions of the historic leader, but it still works to return depth to King’s image.

Harvard Sitkoff

Hill and Wang

2008

288 Pages

Greetings, I borrowed King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop from the Robarts Library at the University of Toronto.

Harvard Sitkoff is an American Historian who taught at the University of New Hampshire where he is currently serving as professor emeritus. Sitkoff is a scholar of the American Civil Rights movement and he has written a number of books on that subject. King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop is his most recent book, and his only biography of a movement figure.

King is a short biography of the celebrated Civil Rights leader. Many scholars have devoted an enormous amount of energy describing King’s life, and if a researcher does not require a highly detailed account of a segment of King’s life then Sitkoff’s concise biography is probably sufficient. This volume devotes the last seven pages of its text to the Sanitation Worker's strike in Memphis, for example, which was the issue King was dealing with at the time of his assassination. Meanwhile the book Going Down Jericho Road by Michael K. Honey, a text that deals solely with the events pertaining to the Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike, is over 400 pages in length. While Sitkoff’s text is quite strong, my only grievance with the book is that he presents the bibliography as a ‘bibliographic essay’, where the references are strung together in paragraphs rather than listed as individual entries. I find this form of referencing to be irritating to search through as the biblographic essay is much more dense, textually, than the traditional form of listed bibliographic references.

King: Pilgrimage to the Mounaintop depicts King as a man who realized his talent for speaking, and was thrust by his parishioners into the spotlight. Sitkoff creates the sense that King was one of those men who was created by history, he had the talents to deal with the issues of his time, but it was his time that formed him into the leader he was. One of the primary value of the book is that it depicts King as a man whose life was fraught with failures. King was motivated to try, the success of his endeavours was never assured, and it was often blocked by circumstance. Despite his Nobel laureate status and his ascension to the position of an unofficial founding father for the current age, King’s life was not a string of relentless success. Sitkoff instead presents King as a man who did not falter in his path, despite occasional failure, towards an egalitarian vision of social harmony.

King adopted Gandhi’s principles of non-violent resistance and applied them to the struggle to attain equal rights for poor blacks in the United States. King worked directly with many impoverished black communities, with varying degrees of achievment, although it was his early work in Selma and Montgomery Alabama that brought him the most success and attention. The civil rights leader’s later successes came from not wavering from his dedication to non-violence. Sitkoff presents King’s voice as diminishing towards the end of the 1960s, as the rise of a black power radicalism emerged with the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, and other radical factions. Converse to King and many of the early civil rights groups, the radical organizations and leaders held much more liberal attitudes towards violence, often preaching it as an unwelcome but necessary part of the racial struggle in America. King developed rhetoric to demonstrate a sympathetic understanding of a black will to violence, but he never condoned such action. According to Sitkoff, however, King was constantly criticized for his proximity to the pro-violent groups, King was still the major figure of the movement even though his adherence to peaceful resistance was losing ground within the overall movement. Shortly before his death, King was held responsible for a march turned riot in Memphis that resulted in the death of a teenager. King was accused by a white media establishment of failing to keep the peace, but King simply could not contain the anger of the poor communities he was trying to organize.

Sitkoff portrays King as an individual who was constantly feeling the tension between the constraining power of the establishment, the detractions of other civil rights factions, the white opposition, and the needs of the poor. Furthermore, Sitkoff presents King as a man who was given to vice as a coping mechanism for dealing with the stresses of his position. The leader’s life was fraught with fear, as King frequently received death threats, and Sitkoff tries to represent the inner battle King must have fought to overcome these terrors. In so doing, Sitkoff creates a glimmer of the sense of what the experience of being a leader of history, may actually feel like.

In current popular culture, King's life has primarily been reduced to the speech he delivered in Washington DC in 1963. Perhaps his image has been flattened further, to merely the line "I have a dream!" When isolated, that line is merely a statement of desire for a boundless future, and can be inserted into a history of such expressions. The line is depoliticized when its isolated from the rest of the speech, and decontextualized when, for example, no one has to remember that, several days after that speech was delivered, a bomb exploded in a predominantly African-American church in Burmingham Alabama, killing four little girls. Now, in popular culture, the moment that line was delivered is almost cast as the moment racial tension broke and race was transcended in America. Media apparitions such as the far-right mouthpiece, Glenn Beck freely appropriate King’s image for their own purposes. Sitkoff’s brief biography is unlikely to successfully compete for dominance with any pop-culture constructions of the historic leader, but it still works to return depth to King’s image.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Labels

united states

(55)

1990s

(25)

history

(21)

1980s

(20)

1960s

(19)

2000s

(18)

1970s

(17)

Canada

(16)

anarchism

(15)

punk

(15)

memoir

(14)

outlaw bikers

(14)

documentary film

(11)

civil rights movement

(10)

new york city

(10)

film

(9)

zines

(9)

19th century

(8)

1950s

(7)

20th century

(7)

black panther party

(7)

irish republican army

(7)

1940s

(6)

2010s

(6)

beats

(6)

essays

(6)

hells angels

(6)

hippies

(6)

journalism

(6)

science-fiction

(6)

street art

(6)

the troubles

(6)

England

(5)

United Kingdom

(5)

anti-globalization

(5)

communalism

(5)

computer hackers

(5)

exhibition catalog

(5)

graffiti

(5)

homeless

(5)

international

(5)

labour strike

(5)

occupy wall street

(5)

organized labour

(5)

quebec

(5)

1930s

(4)

France

(4)

IWW

(4)

biographical drama

(4)

dada

(4)

david graeber

(4)

drama

(4)

interviews

(4)

malcolm x

(4)

novel

(4)

provisional IRA

(4)

psychedelia

(4)

sncc

(4)

sociology

(4)

street gangs

(4)

surrealism

(4)

survivalism

(4)

transcendentalism

(4)

white nationalism

(4)

1920s

(3)

4chan

(3)

BBSs

(3)

Emma Goldman

(3)

Europe

(3)

Karl Marx

(3)

Texas

(3)

Toronto

(3)

anarcho-primitivism

(3)

anarcho-syndicalism

(3)

anonymous

(3)

anthology

(3)

anti-civilization

(3)

autobiography

(3)

banksy

(3)

comedy

(3)

critique

(3)

direct action

(3)

ethnography

(3)

football hooligans

(3)

hacker groups

(3)

hacking

(3)

journalistic

(3)

ku klux klan

(3)

labour

(3)

martin luther king jr

(3)

mongols

(3)

philosophy

(3)

radical right

(3)

reader

(3)

situationism

(3)

student movement

(3)

vagabonds

(3)

white supremacy

(3)

william s burroughs

(3)

/b/

(2)

1910s

(2)

1981 Hunger Strikes

(2)

AFL-CIO

(2)

Alexander Berkman

(2)

American South

(2)

American revolution

(2)

Andre Breton

(2)

Arab Spring

(2)

Australia

(2)

Baltimore

(2)

Cromwell

(2)

English Revolution

(2)

Fidel Castro

(2)

Germany

(2)

Greece

(2)

Levellers

(2)

Manchester

(2)

Marcel Duchamp

(2)

Max Ernst

(2)

Mikhail Bakunin

(2)

Montreal

(2)

NAACP

(2)

Peter Kropotkin

(2)

Portland Oregon

(2)

Ranters

(2)

Robin Hood

(2)

Salvador Dali

(2)

Southern Poverty Law Center

(2)

action film

(2)

animal liberation

(2)

anti-capitalism

(2)

anti-war

(2)

anti-war movements

(2)

article

(2)

aryan nations

(2)

avant-garde

(2)

bandidos motorcycle club

(2)

biography

(2)

black flag

(2)

black power

(2)

blek le rat

(2)

brook farm

(2)

crime drama

(2)

critical mass

(2)

cults

(2)

cultural criticism

(2)

david duke

(2)

design

(2)

diary

(2)

dishwasher pete

(2)

east bay dragons

(2)

eldridge cleaver

(2)

environmentalism

(2)

fan fiction

(2)

gerry adams

(2)

historical drama

(2)

historical survey

(2)

hobos

(2)

how to guide

(2)

indigenous struggle

(2)

internet memes

(2)

ireland

(2)

italy

(2)

jack kerouac

(2)

jared taylor

(2)

john waters

(2)

john zerzan

(2)

julian assange

(2)

keith haring

(2)

mail art

(2)

media criticism

(2)

mohawk warriors

(2)

mole people

(2)

murray bookchin

(2)

musical

(2)

mysticism

(2)

nativism

(2)

new age

(2)

nomadism

(2)

northern ireland

(2)

occupy movement

(2)

official IRA

(2)

oka crisis

(2)

operation black rain

(2)

oral history

(2)

paranoia

(2)

paul goodman

(2)

philip k dick

(2)

phone losers of america

(2)

photobook

(2)

phreaks

(2)

piracy

(2)

posse comitatus

(2)

prank phone calls

(2)

primary source

(2)

revolution

(2)

sabotage

(2)

self-publishing

(2)

shepard fairey

(2)

spain

(2)

student protest

(2)

terrorism

(2)

the order

(2)

travel

(2)

tristan tzara

(2)

true crime

(2)

txt files

(2)

ulrike meinhof

(2)

underground media

(2)

unorganized militias

(2)

1%ers

(1)

17th century

(1)

1860s

(1)

1900s

(1)

1969

(1)

1970

(1)

1972 Bloody Sunday

(1)

1980s. memoir

(1)

2009

(1)

2011

(1)

2600 Magazine

(1)

Alberta

(1)

Alexandros Grigoropoulos

(1)

Amsterdam

(1)

Arthur Segal

(1)

Athens

(1)

Ben Reitman

(1)

Bethel

(1)

Bill Haywood

(1)

Boston

(1)

Brad Carter

(1)

Brendan Hughes

(1)

British Columbia

(1)

Burners

(1)

Burning Man

(1)

CLASSE

(1)

Captain Mission

(1)

Cass Pennant

(1)

Charles Fourier

(1)

Chartists

(1)

Che Guavara

(1)

Christopher Hill

(1)

Christopher Street Liberation Day

(1)

Columbia University

(1)

DOA

(1)

Darkthrone

(1)

David Ervine

(1)

Dead

(1)

December 2008 riots

(1)

Derrick Jensen

(1)

Dial

(1)

Diggers

(1)

Diggers (1650s)

(1)

Dorothea Tanning

(1)

Drop City

(1)

E.D. Nixon

(1)

East Side White Pride

(1)

Edward Winterhalder

(1)

Egypt

(1)

Emiliano Zapata

(1)

Emory Douglas

(1)

Emperor

(1)

Eric Hobsbawm

(1)

Eugene V. Debs

(1)

Exarchia

(1)

FLQ

(1)

Factory Records

(1)

Fenriz

(1)

French Revolution

(1)

GLBT rights

(1)

Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois

(1)

Gandhi

(1)

Gay Activist Alliance

(1)

Geert Lovink

(1)

George Washington

(1)

Georges Janco

(1)

Great Depression

(1)

Groote Keyser

(1)

Harlem

(1)

Haymarket Bombing

(1)

Henry David Thoreau

(1)

Henry Rollins

(1)

Hillel

(1)

Ho-Chi Minh

(1)

Hunter S Thompson

(1)

Hunter S. Thompson

(1)

Idaho

(1)

India

(1)

Indignados

(1)

Inter City Firm

(1)

Irish national liberation army

(1)

Isidore Isou

(1)

Jack Cade

(1)

Jeff Ferrell

(1)

John Humphrey Noyes

(1)

Joy Division

(1)

Kemal Ataturk

(1)

King Alfred

(1)

Konstantina Kuneva

(1)

LETS system

(1)

Labor Party

(1)

Lenin

(1)

Leonora Carrington

(1)

Lettrisme

(1)

Libertatia

(1)

Louis Aragorn

(1)

Luddites

(1)

Madagascar

(1)

Mafiaboy

(1)

Maine

(1)

Mao Tse-Tung

(1)

Maple Spring

(1)

Marcel Janco

(1)

Margaret Fuller

(1)

Mark Rudd

(1)

Martin McGuinnes

(1)

Mayhem

(1)

Michigan Milita

(1)

Moncton

(1)

Montgomery Bus Boycott

(1)

Morris Dees

(1)

Movement Resource Group

(1)

Mulugeta Seraw

(1)

National Film Board

(1)

Ned Kelly

(1)

Netherlands

(1)

New Brunswick

(1)

Norway

(1)

OK Crackers

(1)

Occupy Homes

(1)

Oklahoma

(1)

Oklehoma

(1)

Oneida Community

(1)

Ontario

(1)

Oscar Wilde

(1)

Oslo

(1)

Owen Sound

(1)

Pagans Motorcycle Club

(1)

Palestinian nationalism

(1)

Patrick Henry

(1)

Paul Eluard

(1)

People's Kitchen

(1)

Phalanx Communities

(1)

Philadelphia

(1)

Phillipe Soupault

(1)

Process Church

(1)

Quakers

(1)

Randy Weaver

(1)

Raoul Vaneigem

(1)

Raymond Pettibon

(1)

Rene Magritte

(1)

Robespierre

(1)

Robiespierre

(1)

Romania

(1)

Rome

(1)

Rosa Parks

(1)

Rubell Collection

(1)

Ruby Ridge

(1)

Russian Revolution

(1)

Sacco and Vanzetti

(1)

Samuel Gompers

(1)

Sinn Fein

(1)

Situationist International

(1)

Society for a Democratic Society

(1)

Sojourners for Truth and Justice

(1)

Staughton Lynd

(1)

Surrealists

(1)

Switzerland

(1)

T.A.Z.

(1)

The Rebels (Canada)

(1)

Thessaloniki

(1)

Thomas Paine

(1)

Timothy McVey

(1)

Tobie Gene Levingston

(1)

Tom Metzger

(1)

Toronto Video Activist Collective

(1)

Tunisia

(1)

UVF

(1)

Ulster Volunteer Force

(1)

Ultras

(1)

University of Moncton

(1)

Varg Vikernes

(1)

WWII

(1)

Walt Whitman

(1)

White Citizen's Council

(1)

Wisconsin

(1)

Woody Guthrie

(1)

Workers' Party of Ireland

(1)

Yes Men

(1)

Yolanda Lopez

(1)

Zurich

(1)

abbie hoffman

(1)

abolitionism

(1)

acadian nationalism

(1)

amana

(1)

american renaissance

(1)

anarchist black cross

(1)

anarcho-communism

(1)

andreas baader

(1)

anti-consumerism

(1)

anti-rent movement

(1)

arcades

(1)

arizona

(1)

art book

(1)

art history

(1)

art strike

(1)

assata shakur

(1)

atf

(1)

automatic writing

(1)

bandidos

(1)

bandits

(1)

bartering

(1)

bay area

(1)

bertrand russell

(1)

bicycles

(1)

biker church

(1)

bikies

(1)

black lives matter

(1)

black metal

(1)

black radicalism

(1)

bob black

(1)

bob flanagan

(1)

bobby seale

(1)

bryon gysin

(1)

business

(1)

caledonia conflict

(1)

cats

(1)

chicago

(1)

chicago 68

(1)

chicago 8 trial

(1)

children's book

(1)

chris carlsson

(1)

chris kraus

(1)

church of life after shopping

(1)

church of stop shopping

(1)

civil disobedience

(1)

comic book

(1)

commentary

(1)

commune

(1)

communism

(1)

confidential informants

(1)

conscientious objectiors

(1)

contemporary

(1)

cope2

(1)

core

(1)

correspondence

(1)

crimethinc ex-workers collective

(1)

critical race studies.

(1)

critque

(1)

crossmaglen

(1)

cult of the dead cow

(1)

cultural theory

(1)

culture jamming

(1)

cybercrime

(1)

cycling

(1)

daniel domscheit-berg

(1)

david dellinger

(1)

david watson

(1)

dead kennedys

(1)

debbie goad

(1)

decollage

(1)

dishwashing

(1)

donn teal

(1)

drag

(1)

drill

(1)

drugs

(1)

dumpster diving

(1)

dwelling portably

(1)

ed moloney

(1)

education

(1)

educational

(1)

elliot tiber

(1)

emmet grogan

(1)

environmental movement

(1)

errico malatesta

(1)

fanzines

(1)

fay stender

(1)

feminism

(1)

ferguson

(1)

folklore

(1)

front du liberation du quebec

(1)

gay pride

(1)

general strike

(1)

george jackson

(1)

georges bataille

(1)

gerard lebovici

(1)

gnostic

(1)

graffiti research lab

(1)

guerrilla filmmaking

(1)

guide

(1)

guy debord

(1)

guy fawkes

(1)

hakim bey

(1)

hans kok

(1)

harmonists

(1)

hiphop

(1)

huey newton

(1)

humour

(1)

icarians

(1)

illegal immigration

(1)

immigration movement

(1)

independence movement

(1)

industrial workers of the world

(1)

inspirationalists

(1)

insurrection

(1)

islamophobia

(1)

jay dobyns

(1)

jean baudrillard

(1)

jean-michel basquiat

(1)

jello biafra

(1)

jerry adams

(1)

jerry rubin

(1)

joe david

(1)

johann most

(1)

john birch movement

(1)

john cage

(1)

john lewis

(1)

journal

(1)

judith sulpine

(1)

juvenile literature

(1)

kathy acker

(1)

keffo

(1)

ken kesey

(1)

kenneth rexroth

(1)

know-nothings

(1)

lady pink

(1)

language rights

(1)

lifestyle anarchism

(1)

literature

(1)

london

(1)

london ont

(1)

long kesh

(1)

los angeles

(1)

manifesto

(1)

martha cooper

(1)

marxism

(1)

masculinity

(1)

matthew hale

(1)

max yasgur

(1)

may day

(1)

medgar evers

(1)

merry pranksters

(1)

mexican mafia

(1)

michael hart

(1)

michael lang

(1)

micro-currency

(1)

microcosm publishing

(1)

middle-east

(1)

mini-series

(1)

miss van

(1)

mlk

(1)

mockumentary

(1)

mods and rockers

(1)

moot

(1)

nation of islam

(1)

national vanguard

(1)

native american party

(1)

neal cassady

(1)

neo-confederacy

(1)

neoconservatism

(1)

neoism

(1)

new left

(1)

noam chomsky

(1)

nolympics

(1)

non-violence

(1)

nonsense

(1)

north africa

(1)

notes from nowhere

(1)

obey giant

(1)

occupy london

(1)

occupy oakland

(1)

october crisis

(1)

oral biography

(1)

pacifism

(1)

parecon

(1)

peasant rebellion

(1)

perfectionists

(1)

photomontage

(1)

pirate radio

(1)

pirate utopias

(1)

poachers

(1)

poetry

(1)

polemic

(1)

police brutality

(1)

political science

(1)

popular uprisings

(1)

portland

(1)

post-WWII

(1)

prank

(1)

protest

(1)

radical art

(1)

radical left

(1)

ralph waldo emmerson

(1)

real IRA

(1)

red army faction

(1)

regis debray

(1)

retort (periodical)

(1)

reverend billy

(1)

rock machine

(1)

ruben "doc" cavazos

(1)

san francisco

(1)

scavenging

(1)

script kiddies

(1)

scrounging

(1)

secession

(1)

second vermont republic

(1)

self-published

(1)

semiotext(e)

(1)

sexual politics

(1)

shakers

(1)

shedden massacre

(1)

short stories

(1)

simulation

(1)

slab murphy

(1)

slave revolt

(1)

snake mound occupation

(1)

social ecology

(1)

socialism

(1)

solo angeles

(1)

sonic youth

(1)

sonny barger

(1)

south armagh

(1)

spirituality

(1)

squatting

(1)

stage performance

(1)

stencil graffiti

(1)

stewart home

(1)

sticker art

(1)

stokley charmicael

(1)

stokley charmichael

(1)

stonewall riots

(1)

straight-edge

(1)

street theater

(1)

subgenius

(1)

survey

(1)

sylvere lotringer

(1)

tariq ali

(1)

teacher

(1)

ted kaczynski

(1)

television

(1)

tent city

(1)

terror

(1)

thermidor

(1)

timothy leary

(1)

train-hopping

(1)

tramps

(1)

trickster

(1)

trolling

(1)

tunnel dwellers

(1)

undercover

(1)

underground press

(1)

underground railroad

(1)

uprising

(1)

urban infrastructure

(1)

utopian

(1)

utopian communities

(1)

vegan

(1)

vermont

(1)

war measures act

(1)

warez scene

(1)

weather underground

(1)

white power skinheads

(1)

why? (newspaper)

(1)

wikileaks

(1)

winnipeg

(1)

woodstock

(1)

word salad

(1)

world church of the creator

(1)

yippies

(1)

youth culture

(1)

z communications

(1)